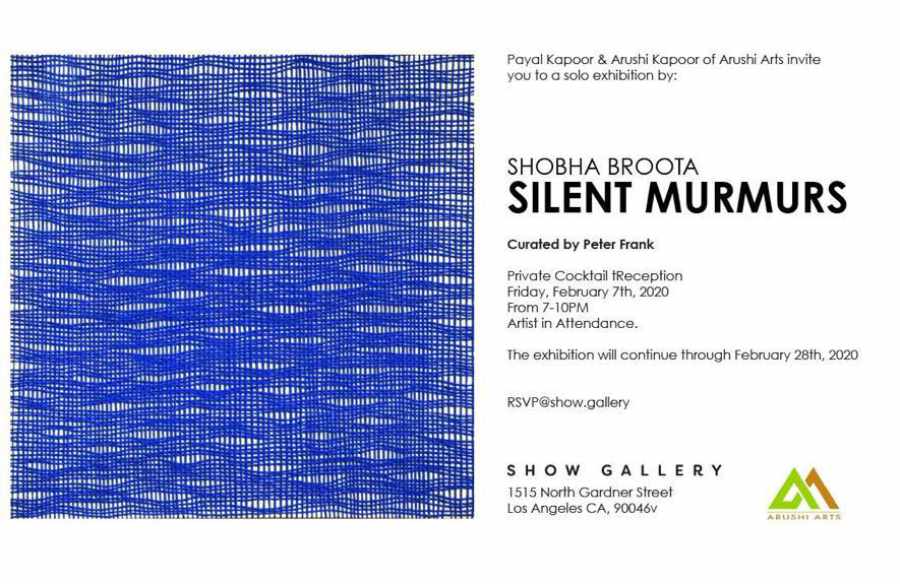

It comes as no surprise to learn that Shobha Broota, one of India’s leading abstract painters, studied traditional Indian vocal music even before she studied art. Indian classical music relies on ready improvisation within a dense system of regulation and, perhaps most importantly, provides performer and listener alike an aural space of thorough absorption, indeed of sonic meditation. Broota’s luminous non-objective canvases and planar objects are designed to bring the viewer into exactly that meditative frame of mind; only here the eyes rather than the ears are focused into a patterned infinity where the sense of self merges with all possible sensibility. The effect is not merely contemplative, but tantric: the ego not only embraces the void but dissolves into it.

The stunning beauty of Broota’s concentric rings, repeated dots, fanning diagonals, and other structures, all rendered in vivid, gentle hues at once reticent and seductive, relaxes the mind’s critical defenses without disarming them. One does not lose oneself equally in every painting or relief. Some viewers might respond more thoroughly to the painted works, others to those pieces fabricated from wool or silk with their tactile inference. Some in the audience may relinquish themselves immediately to the embrace of radiant color and graceful symmetry, others may resist, suspicious of what might at first seem decorative or reductivist. But the works pay their debt early on to Euro-American minimal art, their obvious Western forerunner, and move on to other realms of raffinate experience — the same realms, it can be argued, that the minimalism of tantric painting, several centuries old, once occupied (or, rather, induced). Whatever Broota’s contribution to art history, the contribution of her art to our individual histories is ultimately what comes into sharpest focus — or, if you would, deepest immersion.

Shobha Broota’s artwork, then, is a very personal expression — for each of us in a very different way. Its radicality lies not in their form but in their effect, and in the way that effect manifests individually among those who behold them. To be sure, all art of any substance strikes different chords in different viewers; but Broota’s work, so simple in its graphic display, relies on the slippage, of meaning as well as of experience, between the eyes that fall upon it, and between the minds that fall into it. There comes a moment, in a certain painting, at a certain depth, where one realizes that he or she has left behind not only the world, but those others also looking at the art. You are alone with — within — the work. This is what happens at concerts, you merge with the music and leave everyone behind as the sound unfurls. In Broota’s art it is an atmosphere, a galactic inner space, that unfurls, and into which you hurtle at your own velocity.

Peter Frank

Los Angeles

February 2020